Reflections on Toyota Kata

Early Exposure

I first became aware of the process of Kata in 2004, when I was a Group Leader at Toyota’s Assembly Plant in Derby in the UK. Except I don’t recall it being called ‘kata’ or even that I was being coached through a structured process – it was just how things were done there!

Jumping forward a few years to 2009 I read (positively devoured, in fact), Mike Rother’s seminal book, Toyota Kata: Managing People for Improvement, Adaptiveness and Superior Results. In the book, Rother describes how – using two structured practice routines – Toyota teaches its people to navigate through a series of improvement cycles towards a vision or goal.

Jumping forward a few years to 2009 I read (positively devoured, in fact), Mike Rother’s seminal book, Toyota Kata: Managing People for Improvement, Adaptiveness and Superior Results. In the book, Rother describes how – using two structured practice routines – Toyota teaches its people to navigate through a series of improvement cycles towards a vision or goal.

These practice routines, or ‘Katas’, are designed to give people inexperienced in using the Scientific Method for improvement activity, a guide or prop, to assist them until such a time that their new habits are ingrained and effectively second nature.

Since Rother first published his first book on Kata, it strikes me that Kata is still on the periphery of lean thinking, and that its adoption is quite sporadic – in my experience, even in organisations that consider themselves to be quite ‘Lean mature’. I started to think why this might be the case and began to do some research into factors that might be contributing to the less than over-whelming adoption rates.

Poor take up

Empirical research I did (for the assignment I submitted for my LCS Level 3 certification) found that only 9% of respondents said their organisations were actively using the Kata approach in support of improvement activity.

So what could be the reasons for such poor adoption?

Lack of awareness could be one, but the counter-argument for this is that as far back as 2008 (before Rother’s book was published!) in their book, Toyota Culture: The Heart and Soul of the Toyota Way, Liker and Hoseus described the Toyota Production System to be akin to a DNA helix with a clearly defined Process Value Stream and a People Value Stream. In the People Value Stream they describe in great detail the specific processes Toyota uses to support the development of its people. Tellingly they say:

“They (Toyota Sensei) realise that most ideas for improvement are simply good guesses and need to be verified through experimentation, so they want many experiments to be run by many people working in the process who are constantly monitoring the results of experiments and learning”.

Perhaps another reason that the Kata approach is left ‘on the shelf’ by lean practitioners is because they know that senior managers have little appetite in allowing teams to experiment – to use Scientific Thinking – to help understand and solve problems.

Perhaps another reason that the Kata approach is left ‘on the shelf’ by lean practitioners is because they know that senior managers have little appetite in allowing teams to experiment – to use Scientific Thinking – to help understand and solve problems.

My survey results suggest that, when asked if their company promoted a culture that encouraged a ‘trial and error’ or experimental approach to improvement, respondents scored their organisations 3.6 out of a maximum of 10. A tendency towards risk-aversion and blame culture were given as reasons that inhibit this approach.

Another thought I explored was how ‘western’ leaders differ in their approach to problem-solving than those in ‘eastern’ regions. This complex picture can be summarised in such key differences as a ‘western’ tendency to be more results-oriented (especially in the short-term), and a belief that lean implementation is a defined pathway of tool acquisition and execution. This may be a significant factor in why ‘linear thinking’ is prevalent in the application of ‘Lean’ in the West, resulting in a greater focus on the ‘tools’ than on the human elements of the approach. And perhaps explains why Kata isn’t seen as a core principle in many lean deployments?

Kata Research Group

So, what do we want to learn and develop through the LERC Kata workstream?

- What is the level and nature of the use of Kata in organisations?

- What are the barriers and enablers to Kata’s adoption in organisations?

- What are the critical factors that need to be present in an organisation for Kata to be successful?

- Are those enterprises currently using Kata finding that it is more effective than previous attempts at deploying Lean principles?

- How should Kata be positioned in a wider framework of Lean Thinking tools and techniques? Is there overlap / conflict with other approaches?

I’m delighted to be able to help facilitate this research with the LERC team. Whether you are a self-proclaimed ‘Kata Geek’ or not, please join us as we develop a deep understanding of the effectiveness of Kata, and the conditions required to make it thrive!

I will let Mike Rother have the final word…

“Does the way ahead for developing improvement Kata behaviour in your organisation seem unclear? Are you unsure about what you will need to do to achieve successful culture change? Well, that is exactly how it should be, and if so, I can assure you that you are already on the right track. We cannot know what the path ahead will be, but the improvement Kata shows us a way to deal with and perhaps even enjoy that unpredictable aspect of life!”

Exploring 25 years of Lean Literature

How did the publication of the book The Machine That Changed The World change management thinking? Exploring 25 years of lean literature

How did the publication of the book The Machine That Changed The World change management thinking? Exploring 25 years of lean literature

Download the article >>> Exploring 25 years of lean

Authors:

- Dr Donna Samuel, Lean Academy, SA Partners, Caerphilly, UK.

- Dr Pauline Found, Buckingham Business School, The University of Buckingham, Buckingham, UK.

- Dr Sharon J Williams, Cardiff Business School, Cardiff University, Cardiff, UK.

Researching Lean Themes

Introduction

The short web based questionnaire asked just two main questions, each with an open ended supplementary question, plus four profile related questions. One main question focused on the relative importance of lean research themes, while the other focused on the potential disruptive impact of specific issues on the ability to create a sustainable lean culture.

Prospective respondents were told that its purpose was to obtain feedback and views from the lean practitioner community on lean research themes that are being considered in the development of the lean research agenda and that results will help ensure that research undertaken is relevant to the practitioner community and the issues and challenges being faced.

Importance of Themes

Respondents were asked to indicate how relevant specific research themes and topics were to their organisation in its quest to become a lean enterprise.

The ‘very relevant’ scores are shown in rank order below:

- Nature of lean leadership – 55%

- Sustainability factors & barriers – 52%

- Competency definition, measurement & development – 45%

- Training system methods and structures – 41%

- Service productivity – 38%

- Lean tools and techniques effectiveness – 38%

- Lean evolution in the fourth Industrial Revolution Era – 31%

- Supply chain effectiveness – 31%

- Public value – 30%

- Developing a Lean framework for Big Data Analytics – 29%

When the ‘very relevant’ scores are added to the ‘quite relevant’ scores, the rank order is as follows:

- Nature of lean leadership – 89%

- Sustainability factors & barriers – 83%

- Competency definition, measurement & development – 83%

- Lean tools and techniques effectiveness – 80%

- Service productivity – 73%

- Training system methods and structures – 72%

- Public value – 63%

- Supply chain effectiveness – 60%

- Lean evolution in the fourth Industrial Revolution Era – 55%

- Developing a Lean framework for Big Data Analytics – 55%

While Leadership and Sustainability remain most relevant overall, some themes (highlighted) move up the table when all relevancy answers are taken into account.

Respondents were asked to list other themes they thought could be relevant research topics, which were:

- Lean in research & development

- Realising the benefits of lean

- Customer demand variation

- Deeper exploration of Systems Thinking applied to the public sector.

Potential Disruptive Impact of Issues

Respondents were asked to rank a number of issues in terms of their potential disruptive impact on their organisation’s ability to create a sustainable lean/continuous improvement culture over the next three years. The rank order of average scores is shown below (5= very high impact)

- Lack of management interest in lean thinking/CI – 3.92

- Inadequate strategy formulation and deployment – 3.66

- Lean skills shortage in workforce – 3.32

- Measures used to gauge business success – 3.31

- Lack of funds for lean training – 3.09

- Poor productivity levels – 3.05

- Technological change, eg Big Data, digitisation – 3.03

- High staff turnover – 2.95

- Product/service innovations – 2.95

- Robotic process automation/AI – 2.92

- Market structure change, eg mergers, acquisitions – 2.80

- Public spending cuts – 2.55

- Increased competition – 2.54

- Political factors, eg Brexit – 2.42

- Fourth Industrial Revolution -2.29

- Globalisation – 2.28

Research Method Details

- Data collection: Web based questionnaire, via JISC

- Date collected: December 2017 to March 2018

- Number of respondents: 66

Respondent Profile

The representativeness of the results can be judged from studying the profile of respondents.

Sector

Region

Respondent role

Organisation size

Learning to Evolve – A Review of Contemporary Lean Thinking (2004)

Abstract

The application of lean thinking has made a significant impact both in academic and industrial circles over the last decade. Fostered by a rapid spread into many other industry sectors beyond the automotive industry, there has been a significant development of the lean concept. Despite successful applications in a range of settings however, the lean approach has been criticised on many accounts, such as the lack of human integration or its limited applicability outside high-volume repetitive manufacturing environments.

The resulting lack of definition has led to confusion and fuzzy boundaries with other management concepts. Summarising the lean evolution, this paper comments on approaches that have sought to address some of the earlier gaps in lean thinking. Linking the evolution of lean thinking to the contingency and learning organisation schools of thought, the objective of this paper is to provide a framework for understanding the evolution of lean not only as a concept, but also its implementation within an organisation, and point out areas for future research.

Download the paper

Click to download: Learning to Evolve

Case Study: NHS Blood & Transplant

Background

Since 2008, the UK’s NHS Blood and Transplant (NHSBT) has been successful in using lean tools to become a more effective and efficient service and from 2013 the approach has been used to drive improvements in the Histocompatibility and Immunogenetics (H&I) function.

The focus of the H&I work was a national Value Steam Analysis (VSA) of the laboratory network, which consists of six laboratories across England. VSA is performed annually to focus CI activity and one outcome from the initial national VSA identified that changes in laboratory accreditation standards required the addition of a purity assessment method in the Chimerism service. Chimerism is a valuable tool in the assessment of engraftment and graft failure post-Haematopoietic cell transplant.

It was shown that a new cell separation method was required, as it was not possible to adhere to the new accreditation standards with the existing method. An alternate method for cell separation was evaluated, validated and implemented (by established NHSBT change management process).

The newly implemented method proved to be more involved than that previously employed method from comparison of the flow, touch and Takt times. At this time a steady 20% increase in annual workload was observed, with no additional staff resource was available and the method was associated with a sample repeat rate of greater than 60%.

Getting Started

Adapting to change

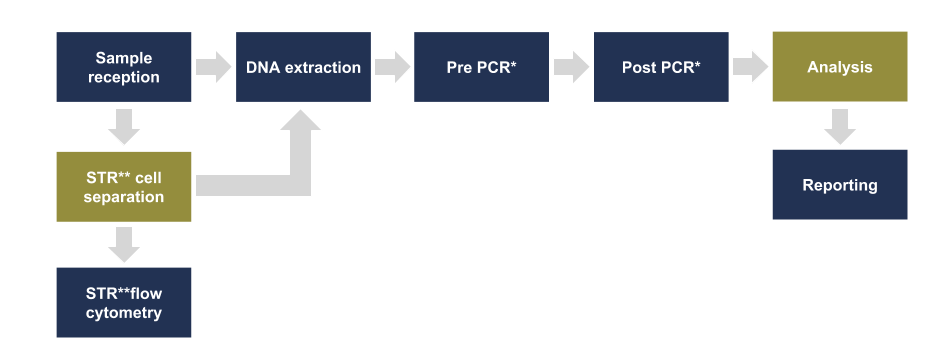

A chimerism value stream was created (figure 1) which prompted a Rapid Improvement Event (RIE) involving staff of all grades from multiple laboratories. Through the use of lean tools (including A3, 8 wastes, process mapping, gap analysis and standard work) a plan for short and long term objectives for Chimerism was agreed in order to adhere to good practice guidelines and accreditation standards.

The RIE was held over five days and led by a colleague who was specifically chosen due to no direct involvement in the chimerism process. The team consisted of representative staff from all grades performing the process across the NHSBT H&I network. This team was joined by an in-house CI representative, a ‘fresh pair of eyes’ from another pathology speciality and a member of the Quality Assurance department.

Standard work was established for each cell and potential bottlenecks were identified (automated extraction platform and genetic analyser due to run capacity). As a result, optimal batch sizes for each cell was agreed to work towards a pull system.

Figure 1 – Chimerism Value Stream

Figure 1: An overview of the cells required in the chimerism value stream. The cells highlighted in orange are exclusive to the chimerism process. All the remaining cells, highlighted in blue, accommodate multiple values streams.

*Polymerase Chain Reaction **Short Tandem Repeat

Removal of waste

Review of the value and non-value added steps identified improvements to the process that could be made immediately – the ‘quick wins’. For example, all of the patient data was stored in increasing large paper files, which were just duplications of raw data and analysis already held in electronic format. Organisation of the local shared storage (backed up on network) allowed easy access to historical data. As a result, each paper file was discarded in preference of an electronic folder for each patient.

Addressing the repeat rate

Standard work provided the platform by which the variability in the process was removed. This included standardising the DNA concentration, optimising the polymerase chain reaction process and creating a standard approach to analysis

Reagent review

A review of other known issues in the process identified that problems consistently arose with supply from commercial companies for key reagents. Where possible these have been replaced with validated in-house alternatives.

Semi-automated analysis

A commercial software package was validated for routine use to reduce potential transcription errors. It also allowed user audit and individual access levels to be set while also providing a standard analysis for all transplant recipients regardless of operator. As an added bonus, statistical analysis and trending of results was more readily available for ISO15189 compliance.

Review of cell separation

A steady increase in workload had pushed the cell separation method to capacity. No immediate alternative was available, but after consultation with suppliers a new robust method was created in collaboration with a third party by adaptation of their existing repertoire. This new method has been validated and implemented across the network.

Study & Measurement of the Lean Improvements

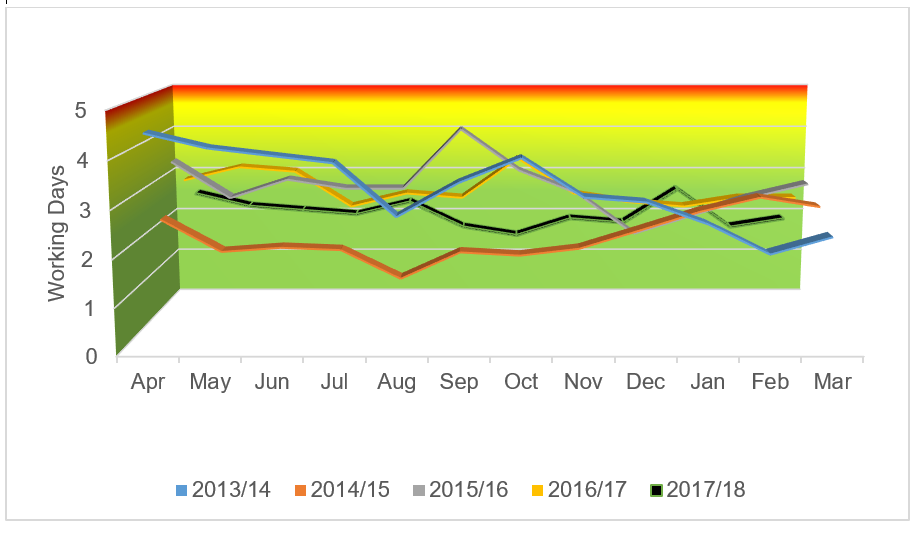

The primary impacts of the improvements on the chimerism service were measured by laboratory Key Performance Indicators (KPIs). KPIs include the number of referrals received, the mean sample turnaround time (TAT) from receipt in the laboratory to clinical report being issued and how many samples failed to meet service level agreed targets (not reported within 5 working days of receipt). These KPIs also contribute to the overall performance of the laboratory, which is openly reported on a monthly and annual basis.

As each improvement has been implemented, standard work has been reviewed to optimise performance. Performance of the chimerism service is trended (KPIs, mean TAT, repeat rates) and discussed in monthly laboratory section reports. Trends have been incorporated into a visual management display.

Results

CI – What does it look like?

Since the initial RIE and a need to address shortcomings in the chimerism process, continuous improvements have been suggested, reviewed and implemented over the last five years (figure 2).

Figure 2 – Time line of interventions in the chimerism process

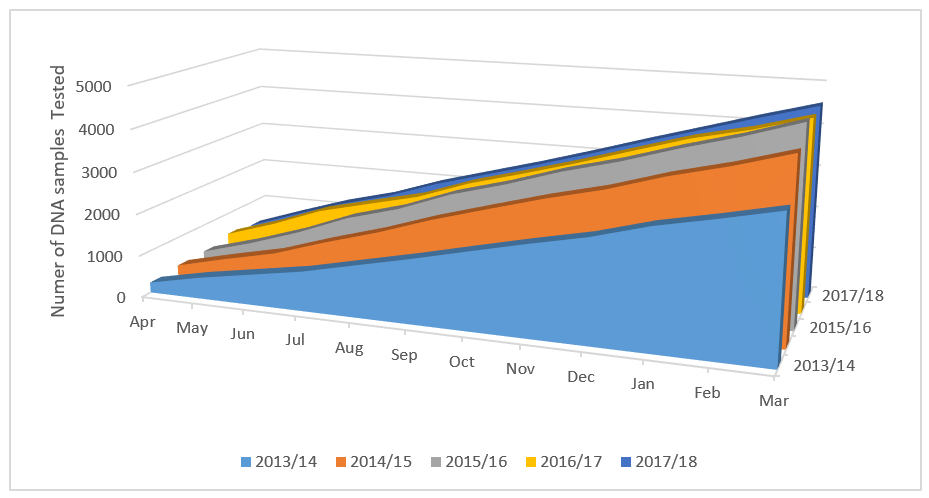

Over the five years that CI has been actively applied to this process, an increased sample workload has been observed (figure 3), while at the same time sample TAT has remained within both service level agreements and recommendations from the best practice guidelines (figure 4).

Figure 3 – Total number of chimerism DNA samples analysed annually

Figure 4 – Mean chimerism sample turnaround (TAT)

Applying CI in the real world

Since CI has been adopted in the laboratory there has been unintended contextual change within the laboratory service, including new equipment, changing/overlapping process value streams, as well as change to the footprint and layout of the laboratory. All of these events have had an impact on standard work.

By utilising CI during these changes the laboratory has observed positive outcomes, such as increased capacity (e.g. more suitable equipment, management its use) and less waste (e.g. motion due to a smaller footprint). CI activity in chimerism has impacted other parallel value streams that utilise shared cells. In these situations, all affected processes have been considered when optimising both standard work and batch sizes.

Counting the £’s?

The costings in the chimerism process have been reviewed at the end of each financial year throughout these improvements (inclusive of staff time, reagents, asset maintenance and software licencing). They have shown the cost per sample has remained consistent allowing the chimerism service to remain financially viable without additional cost to the customer/user, which is in-keeping with NHSBT financial planning.

By implementing standard work, extra capacity has been created within the process to accommodate a potential 70% increase on current workload. This has been achieved with no increase in staffing provision or running costs.

Discussion

Summary

Continual improvement and optimisation of the chimerism method has produced a high quality, low cost, rapid throughput clinical service. Standard work has been defined, KPIs are compliant and positive feedback has been received from both laboratory staff and users. One service user has even lodged an official appreciation of the current service provision through the hospital liaison compliment pathway.

Attention has also been given to the human dimension and small adjustments have been continually suggested and tried based on staff feedback, as well as more major changes such as change of cell separation technique (implementation of alternative technique), modification/optimisation of cell composition/layout (e.g. set-up/orientation and location of cell separation) and work flow within multi-functional cells (e.g. use of flow cytometer and genetic analyser).

Observed Limitations

The irregular work flow due to the user clinic times, the associated time limits of sample processing time given in the best practice guidelines and perceived clinical urgency have, as yet, prevented the process from being a true ‘pull’ system. To date there have been ongoing discussions with the service users to move the clinics and even workflow.

Stumbling blocks and learning points

At the start of the improvement process the CI and lean methodologies were not very well cascaded and were applied in a top-down fashion. The resulting lack of awareness and explanation to justify early interventions created an air of unrest and wariness. After the initial RIE there was also resistance to further CI activity in the process, as to many both in the laboratory and in directorate management, it was viewed as ‘we have already done that process’.

Parallel, stand-alone RIEs targeting individual laboratory cells that accommodate multiple process value streams have impacted and often hindered improvements and standard work already implemented.

These early issues have been largely overcome by involvement of all staff in the CI process and focus on the practical application, where the benefits can be seen day-to-day, not only on A3’s and spreadsheets. The interaction/overlap of value streams has been addressed by including all stakeholders for comments feedback throughout CI activity, from planning to implementation.

Finally, organisational restrictions within NHSBT, due to the structure and legality of financing and tendering within NHSBT, the potential of CI tools such as PDSA is yet to be fully realised. For instance, improvements that affect the testing process cannot only be put into place locally due to potential for non-compliance with TPS51/ISO15189 and significant process deviations/alterations could require reassessment laboratory accreditation bodies.

Author’s final thoughts & reflections

While initially CI activity within NHSBT was very much ‘by the book’, over time there has been more ‘blending’ of the concepts with existing NHSBT processes of controlling and documenting change. This ‘blending’ of CI and quality systems within organisational practice is assisting in positive, ongoing culture change.

In support continued CI ‘super-user groups’ have been created within the organisation, by which each department/stakeholder has a nominated spokesperson for each value stream who meet periodically to update and discuss local CI activity, reaffirm agreed standard work nationally and feedback locally.

In my opinion, without the described improvements and visible evidence of a shift in culture/attitude towards CI, the chimerism service would either no longer be financially sustainable or clinically relevant. I hope that this brief report may be of use or offer reassurance to those implementing or supporting a CI ethos by showing that big changes can be made with small manageable steps.

Value Confusion: Lean in Public Services

Introduction

For well over a decade continuous improvement approaches have been formally applied in the public sector in the UK and elsewhere, in an attempt to improve service quality and streamline processes, often in response to cuts in public expenditure budgets imposed by governments.

Many public services in the UK – including defence, healthcare, police, higher education, central and local government – have now, to a greater or lesser extent, implemented continuous improvement (CI) programmes of various shapes and sizes. However, while there are numerous examples of successful initiatives at a process level, questions remain about whether real systemic changes are being made that will produce the long term sustainable CI culture desired.

This article examines the nature of the lean thinking that has been embraced and calls for a debate on the development of a new definition of lean for public services. It contends that the adoption of an unadapted lean approach that is primarily geared for the private competitive market has meant that public service organisations have misunderstood the nature of value in the public sector, which has created counter-productive distractions and raises issues on lean’s ability to help engineer long term, systemic change.

Lean & Competitive Advantage

This discussion about lean’s role in improving public services starts with examining the purpose of lean thinking and lean methods. The roots of contemporary lean thinking can be traced to the development of the Toyota Production System (TPS) after the second world war and for Taiichi Ohno – Toyota’s chief engineer and architect of the system – it can reasonably be deduced that the ultimate aim of TPS was to create competitive advantage for Toyota, so that buyers of cars chose a Toyota model over those of its competitors.

This was achieved by producing a vehicle that delivered clear value for customers in terms of its cost, quality, reliability, design, performance and so on. The production system’s design was influenced by a post-war environment characterised by shortages and constraints and TPS’s particular ability was to be effective in removing waste from processes and creating flow, thus enhancing customer value adding activities and so creating additional capacity that could be used to sell more cars and expand the business.

The lean approach, as it was later termed by Womack, Jones and Roos, based on TPS principles fitted perfectly into the free market competitive model and from the 1980’s many companies, starting with those in the automotive and aerospace sectors readily attempted to embrace the ideas. Thus contemporary lean thinking became a common feature in many businesses strategies and was able to provide an actionable implementation framework that could be adapted for different business environments and sectors.

The lean approach, as it was later termed by Womack, Jones and Roos, based on TPS principles fitted perfectly into the free market competitive model and from the 1980’s many companies, starting with those in the automotive and aerospace sectors readily attempted to embrace the ideas. Thus contemporary lean thinking became a common feature in many businesses strategies and was able to provide an actionable implementation framework that could be adapted for different business environments and sectors.

The essence of the free market model is that the customer is able to choose among competing offerings and will part with his or her money to the producer that can deliver the greatest perceived value. This classic model positions the private consumer – the customer – as the arbiter of value, whose decisions will ensure that competing businesses will strive to be more effective in meeting his or her needs and delivering the right products at the right prices.

Marketisation of Public Services

UK public policy in the 1980’s was dominated by the neo-liberal thinking of Prime Minister Thatcher and her Conservative governments, which placed a strong emphasis on the virtues of competition and a view that the size and influence of the state should be reduced. Public services were considered bloated, with inherent inefficiencies and a drag on economic growth.

New Public Management (NPM) emerged as the supporting doctrine to this policy, that advocated the imposition in the public sector of management techniques and practices drawn mainly from the private sector, as according to NPM greater market orientation would lead to better cost-efficiency, with public servants becoming responsive to customers, rather than clients and constituents, with the mechanisms for achieving policy objectives being market driven.

NPM reforms shifted the emphasis from traditional public administration to public management and this included decentralisation and devolution of budgets and control, the increasing use of markets and competition in the provision of public services (e.g., contracting out and other market-type mechanisms), and increasing emphasis on performance, outputs and a customer orientation.

Some parts of the public sector left it completely through privatisations, such as utilities, transportation and telecommunications; semi-autonomous agencies were created, such as the DVLA and outsourcing major capital projects through private finance initiatives became common.

The customer became further entrenched in the public sector psyche when John Major’s government introduced the Citizen’s Charter in 1991, which was an award granted to institutions for exceptional public service. As its website stated, “Charter Mark is unique among quality improvement tools in that it puts the customer first”. Its self-assessment toolkit contained six criteria, the second being actively engaging with your customers, partners and staff.

The customer became further entrenched in the public sector psyche when John Major’s government introduced the Citizen’s Charter in 1991, which was an award granted to institutions for exceptional public service. As its website stated, “Charter Mark is unique among quality improvement tools in that it puts the customer first”. Its self-assessment toolkit contained six criteria, the second being actively engaging with your customers, partners and staff.

The Citizen’s Charter was replaced in 2005 by the Customer Service Excellence standard, led by the Cabinet Office, which aimed to “bring professional, high-level customer service concepts into common currency with every customer service by offering a unique improvement tool to help those delivering services put their customers at the core of what they do”. This offered public sector organisations the opportunity to be recognised for achieving Customer Service Excellence, assessed against five criteria, which included ‘customer insight’. To date, several hundred public sector organisations are listed on its website as having achieved Customer Service Excellence.

When the formalised and packaged versions of contemporary lean thinking and CI appeared from the 1990’s, it was a logical step for public sector organisations to adopt these approaches as part of the NPM agenda, especially as continuous improvement was integral to initiatives such as Citizen’s Charter and Customer Service Excellence, as these could help them cope with increasing demand for their services, coupled with reducing budgets and the drive to be customer focussed. Techniques to reduce waste and costs were particularly attractive, even if the resultant released capacity could rarely be used to ‘grow the business’ as it could be in the private sector.

Thus public services readily and enthusiastically embraced all aspects of lean philosophy, integral to which was a market orientation, where the identification and delivery of customer value was paramount.

The Nature of Value & the Customer in Public Services

A process is a process, whether it is in the private or public sector and so it can be argued that process thinking, as defined by System Thinking advocates such as W Edwards Deming, is equally applicable to both, since waste removal, improving quality, reducing lead time and enhancing flow are universal aims.

So while it seems reasonable for public services to use the techniques at a process level to produce some public good, it is argued that by including an explicit customer orientation, it leads to a range of problems.

A key issue is the NPM contention that there are customers in public services for whom value is identified and then delivered. The classic characteristics of customers is their ability to choose between different products and suppliers and spend their money according to the offering that delivers the greatest perceived value. However, in this sense, a customer rarely exists in a public sector context.

Instead, according to writers such as Teeuwen, they are citizens, who can have several roles at different times, including that of user, subject, voter and partner; occasionally, the citizen can be a customer, such as when choosing among transportation options, but it is not the dominant role. To this list could be added patient and prisoner and even obligatee, as Mark Moore describes taxpayers, who clearly have no individual say in taxation, but simply an obligation to pay up. In most of the roles, the individual citizen does not ‘specify the value that is to be delivered’ and has no choice in service provider.

Therefore, it is suggested that the concept of an individual customer deciding on what constitutes value is flawed in a public sector context. This can distort service design, lead to the use of inappropriate or unhelpful measurements with the numerical quantification of quality through targets, create expectations in citizens that cannot be met (leading to frustration and dissatisfaction) and lead to confusion regarding the true purpose of the function or service.

Public Value, not Customer Value

Mark Moore in his seminal work Creating Public Value (1995) recognised the problem that the public sector manager has in working out the value question. Whereas his or her private sector counterpart has a clear idea that the individual consumer is the ‘arbiter of value’ and makes choices on buying competing products based on the perceived value delivered, in the public sector he contends that the arbiter of value is not the individual, but the collective – that is, broadly society in general, acting he says “through the instrumentality of representative government” – and likely to be made up of service users, tax payers, service providers, elected officials, treasury and media.

Mark Moore in his seminal work Creating Public Value (1995) recognised the problem that the public sector manager has in working out the value question. Whereas his or her private sector counterpart has a clear idea that the individual consumer is the ‘arbiter of value’ and makes choices on buying competing products based on the perceived value delivered, in the public sector he contends that the arbiter of value is not the individual, but the collective – that is, broadly society in general, acting he says “through the instrumentality of representative government” – and likely to be made up of service users, tax payers, service providers, elected officials, treasury and media.

Identifying what value to produce for a public service therefore has little to do with an examination of an individual’s needs and preferences. There is also no requirement to win custom and market share through a variety of product delighters, innovations and exceptional customer service.

The notion of public value has echoes of the 19th century Utilitarianism philosophy of Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill, which stated that the goal of human conduct, laws, and institutions should be to produce the greatest happiness of the greatest number. Other significant contributors to the public service value debate in the UK include John Benington at Warwick University (who has collaborated with Moore) and John Seddon, whose CHECK improvement methodology focuses on the need to identify purpose as a prime initial task in service improvement, rather than go down the customer/value route. Identifying purpose appears to have strong resonance with public value.

Identifying public value is not an easy proposition and because decisions are almost always about how to allocate scarce resources, there will be compromise and invariably an individual’s demands will be subordinate to those of society in general.

Moore contends that the pursuit of public value aims requires the support of key external stakeholders, such as government, partners, users, interest groups and donors. Public sector decision makers must be accountable to these groups and to engage them in an ongoing dialogue and build a coalition of support to create this platform of legitimacy.

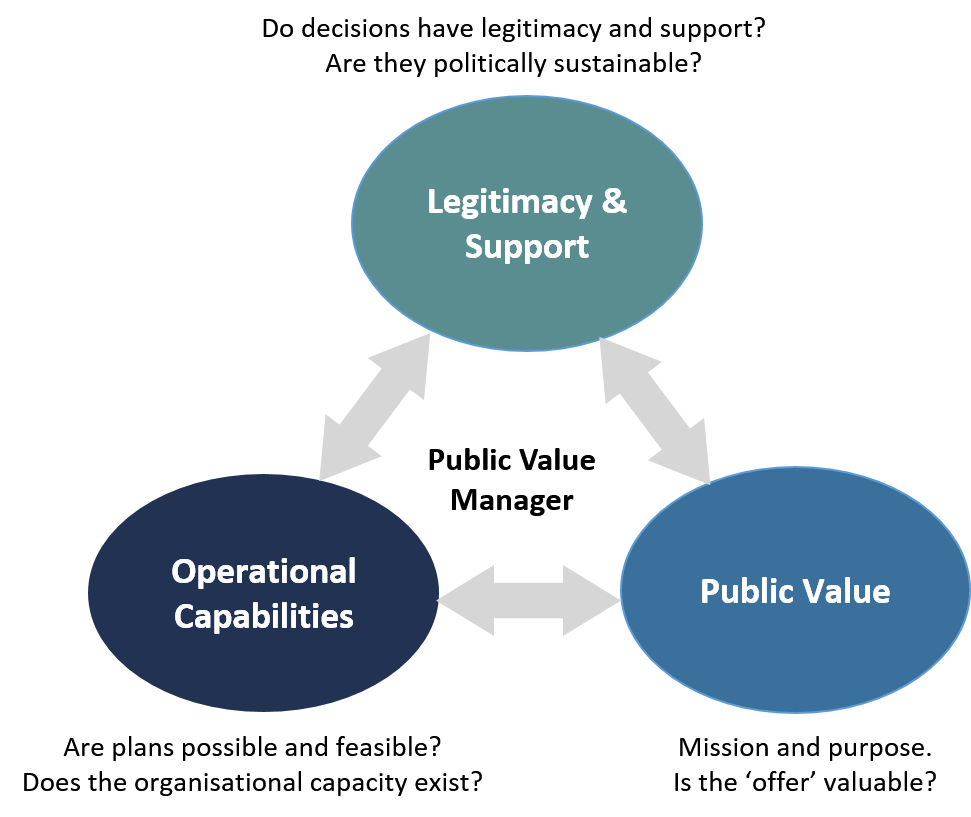

He describes a “strategic triangle”, which represents the dimensions that the public service manager needs to consider in developing a course of action, comprising of the authorising or political environment (legitimacy and support), the operational capacity and the public value (purpose). The proposition in the strategic triangle is that purpose, capacity and legitimacy must be aligned in order to provide the public manager with the necessary authority to create public value through a particular course of action.

Service v. Value

As a result of the NPM agenda, citizens have been led to believe that they are customers of public services, just like they are customers of private businesses and therefore have the same service expectations of public services as when they transact with, for example, retailers John Lewis or Amazon. Similarly, public sector employees have been encouraged to treat the recipients of their services like private sector customers.

This does not mean that public services should not strive to deliver a productive and positive experience to its users, patients, obligatees etc., especially as the outcome of effective process thinking should supply exactly that. As taxpayers, citizens have a reasonable expectation to receive quick, effective and courteous service, but this may have little to do with delivering public value or in achieving its prime purpose.

Indeed, public value is often at odds with private value; consider airport runway expansion in the south east of England, the route of the HS2 train from London to Birmingham, the creation of dedicated cancer drug funds, the gritting of roads in icy conditions and the building of flood defences.

Many public service measures, such as in healthcare, have an explicit customer service orientation and a significant amount of debate and political energy is spent scrutinising these. This is not to say that waiting times for treatment or answering a phone call are not relevant, but that they distract from the important question of assessing and understanding the public value that the particular service should strive to deliver.

HM Revenue & Customs (HMRC) regularly receives significant media and public criticism and a report by the National Audit Office in 2012 into its customer service performance concluded that “while the department has made some welcome improvements to its arrangements for answering calls from the public, its current performance represents poor value for money for customers.”

In 2014-15, HMRC collected a record £518 billion in total tax revenues, employing some 65,000 people. In 2005-06, it collected £404 billion with around 104,000 staff; this means that over a decade it has collected 25% more revenue with 38% fewer staff. It has also made cost savings of £991 million over the past four years. HMRC delivers public value by maximising the tax take using as few as resources as practical, though clearly it does have service obligations to its users.

Interestingly, the National Audit Office report comments that “HMRC faces difficult decisions about whether it should aspire to meet the service performance standards of a commercial organization. It could do only by spending significantly more money or becoming substantially more cost effective.” This is the nub of the dilemma faced by many public services and a key question is whether it should indeed strive to be like a commercial organisation and expend more and more resources in doing so. However, service should not be confused with value.

In the private sector there usually a clear relationship between the price paid and the service received. The Kano model refers to performance or linear attributes of an offering – ‘more is better’ – where increased functionality or quality of execution will result in increased customer satisfaction. For example, we can choose the speed of delivery of an online purchase by selecting either the free (3 to 5 days), standard (2 days) or premium (next day) service and we will make a conscious decision to pay for the one we desire.

This scenario takes place in some UK public services, such as obtaining a new passport, where there are differently priced one week Fast Track service and one day Premium service, though in most public services a direct service-price relationship does not exist.

Conclusions & Future Discussion

The classic lean thinking approach that emerged from TPS is ideally suited to organisations operating in a competitive market environment because of its focus on customer value, its ability to help create competitive advantage, grow market share and ultimately enhance shareholder value. This article contends that the wholesale adoption of this approach by public services is inappropriate, as it does not recognise the difference between private value and public value.

Just as there was a debate in the early 2000’s about whether the lean thinking that was developed and used in manufacturing was suitable for service environments, there needs to be a debate about how it should be adapted for public services and in particular the move towards adopting a public value perspective.

The following suggestions can help inform this debate:

- Lean practitioners in public services should move away from an overt focus on individual customers and the value they demand. Those using Womack and Jones’ first lean principle (‘specify value from the standpoint of the customer’) should adapt it so that the emphasis is on specifying public value that is to be delivered, linked to the purpose of the organisation.

- There needs to be a redefinition of what it means to be a customer of public services; while it is probably too late and counter-productive to abandon the term customer, a new specific public service lean vocabulary will help provide clarification. As Mark Moore comments “the individual who matters is not a person who thinks of themselves as a customer, but as a citizen”.

- Lean leadership in the public sector should primarily focus on understanding and identifying public value. Mangers need to focus specifying the public value that they are trying to deliver and make it clear that this can be different or even in opposition to private value. The key question that a lean manager needs to ask, according to Benington and Moore, is not what does the public most value? but what adds most value to the public sphere?

- The recipients of public services – citizens – need to be educated as to what they can reasonably expect from the public sector in terms of service levels and understand that when they ‘consume’ public services, they are not customers in the same way as when they consume in the private market; they do not have the same rights, advantages or privileges. The level of service provided in delivering services needs to be balanced against the cost of providing it. Citizens also need to understand that public value will sometimes be at odds with private value.

- Public services generally do not present products to a market in the same way that private companies do, the latter then plotting the optimum value stream for delivery to the customer. Rather, they usually wait for demand for services and react; this suggests there should be less emphasis on value stream management and more on demand analysis and management – with a greater emphasis on understanding the nature of the demand (quantity and quality), proactively attempting to limit and control it in many circumstances.

Few would argue that effectively applied process thinking cannot have a positive role to play in improving public services and it is contended that adopting a public value perspective will enhance its overall impact.

But the shift from private value to public value is not without its challenges; several decades of NPM thinking has created a mindset that may be difficult to change and moving to more utilitarian position in an age of individualism may be a daunting prospect. Mark Moore says that a key reason why public value is a challenging idea is because it brings us out of the world of the individual and back into the world of interdependence and the collective; and that, he claims, “runs contrary to the direction that everyone seems to be going in”.

References & Further Reading

Download a pdf version of this article

Watch a Mark Moore video in the LCS website Video area.

Building our Future: Transforming the way HMRC serves the UK (2015), HMRC

Creating Public Value (1995), Mark Moore

Customer Service Excellence website: www.customerserviceexcellence.uk.com

Freedom from Command & Control (2005), John Seddon

Lean for the Public Sector (2011), Teeuwen

Lean Thinking (1995), Womack & Jones

National Archives, Charter Mark website: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20040104233104/cabinetoffice.gov.uk/chartermark/

National Audit office website: www.nao.org.uk

Public Sector Management (2012) Norman Flynn

Public Value: Theory and Practice Paperback (2010), Benington & Moore

Service Systems Toolbox (2012), John Bicheno

Systems Thinking in the Public Sector (2010), John Seddon

The Guardian: www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2016/mar/02/narcissism-epidemic-self-obsession-attention-seeking-oversharing

The Machine that Changed the World (1990), Womack, Jones & Roos

The Case for Open Source Lean

Coming in 2019.